Henrich: The Bitcoin Hedge Myth

Authored by Sven Henrich via NorthmanTrader.com,

Buyers of Bitcoin have seen fantastic results in the past year since the lows of March 2020. That is until the middle of this month as price has dropped a bit. Whether it’s just a momentary hiccup or just another set up to new highs is not the point of this article.

Rather I’d like to discuss a common point that is made about Bitcoin: That it is a store of value, a hedge against the global fiat printing system run by central banks.

Now conceptually one can make anything a store of value if enough people agree that it is, especially if there is limited supply as Bitcoin is structured to be with only 21M possible Bitcoins to be mined. We’ve seen this store of value concept play out for centuries throughout societies. Think stamp collecting. The rarer a stamp the higher its value, especially if collectors think so, even though to most people it’s just a piece of paper with print on it. Others disagree and bid enormous amounts of money on a rare stamp. Value is in eye of the beholder.

One can say the same thing about bottles of wine. People have and will continue to pay thousands, even hundreds of thousands of dollars for rare wines. Happens all the time.

Heck, in many of these cases the wine is not purchased to drink (i.e. be used as a currency, but rather it is a collector’s item to be kept in a wine cellar. A store of value, something a collector may even auction off for profit at a later time. After all, a particular vintage or rare bottle of wine can’t be duplicated and if enough people are interested in it its value is likely to increase.

Fine. If that’s what people buy Bitcoin for, as a store of value who am I to argue? Have at it. As long as people want it and as long as the supply is limited price can appreciate. No different to wines or stamps I suppose.

But is it a hedge against the global fiat system? For now, as Bitcoin has seen such incredible price appreciation, the answer will most definitely be yes, especially by adherents, especially after they have seen massive price gains versus fiat and even the stock market.

But massive price gains or even rapid adoption and/or popularity are not a validation of a long term thesis. Indeed many times massive price gains entice belief in validation when there is none with no predictive value of future success. Think MySpace. It was the first winner in the internet social media world. It still exists but is totally irrelevant in today’s world. AOL? Yahoo? All early winners in the internet world all irrelevant today. But they all had one thing in common: Vast price appreciations with people chasing extremely high valuations that ultimately didn’t prove to be rooted in reality.

Once people believe absolutely in an investment idea that appears validated by vast price appreciation the FOMO and hype becomes so unbearable that even the smartest people on the planet will end up jumping on it. No more famous example than Isaac Newton, arguably the smartest human to have ever lived, yet even he got caught up in the South Sea bubble and ended up having his investment head handed to him.

The larger point: Even if something is highly popular and new at the beginning, even a new technology, it’s not a guarantee it’ll be a winner. Sentiment is fickle.

There are other stories of success of course and we all know who they, think $AMZN, and $GOOGL for example.

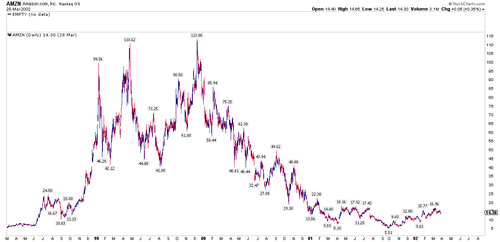

If you bet on $AMZN early on and never sold you’re still laughing. Even though you would’ve had to endure a devastating drawdown early on:

If you bought $AMZN above $50 or above $100 in 1999/2000 and saw it drop below $6 in 2001, you were probably not a happy camper. But $AMZN was one of the best buys ever.

And time clarifies everything. Bitcoin doesn’t have to worry about earnings growth or revenues, it only has to worry about relentless adoption, maintaining sentiment and regulation I suppose. I’m not even going to pretend to want to predict the future so I won’t.

Rather I want to focus on what I can see and test the hedge argument and here is where it gets rather murky. Why? Because as long as Bitcoin keeps running higher everyone is convinced it is a hedge.

I submit the hedge argument is entirely unproven. Yes, percentage wise Bitcoin has performed tremendously on the way up since last year. But everything in our liquidity soaked world has performed well and gone up.

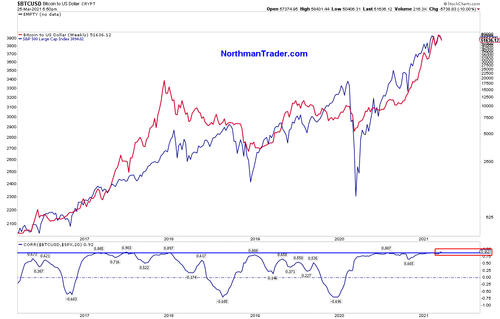

Indeed, the other day I highlighted a flow chart of Bitcoin versus $SPX:

Don’t @ me about % size moves, but weekly flow correlation between $SPX and #Bitcoin has now moved to its highest level ever.

In other news, BofA today: “the main argument for #Bitcoin is not diversification, stable returns or inflation protection, but sheer price appreciation”. pic.twitter.com/0ADdMm6KCx

— Sven Henrich (@NorthmanTrader) March 17, 2021

The basic point: Equities bottomed last year in March so did Bitcoin. Corrections in equities and in Bitcoin and equities tend to occur at the same time, as do new highs.

Case in point in 2021 so far: Markets made new highs in January, so did Bitcoin. The same was true in February and in March and corrections flowed alongside of each other.

Indeed this week again the same:

The correlation indicator sitting at an extreme high of 0.92.

The potential implication: It’s all the same trade albeit Bitcoin being the more volatile on the way up and on the way down.

After all excess liquidity is trying to find a home in superior returns. Which makes this chart actually a bit ironic for then Bitcoin is not a hedge but rather Bit coin has nothing but having jumped on the same liquidity train. And given it being unburdened by any fundamental performance metrics such as earnings it succeeds in vast price appreciation as more and more people jump on the train while big whales are cornering the supply by making investments in the hundreds of millions and/or billions of dollars in a limited supply universe. The perfect Ponzi in that sense. I’m not claiming Bitcoin is a Ponzi, as I said I can’t predict the future, but it has all the marketing elements of it. Price validation, relentless pumping, cornering of supply and a self fulfilling cycle of validation in the eyes of adherents as prices keep jumping and people keep chasing.

But here’s what Bitcoin hasn’t proved in my eyes: That it’s a hedge, for as long as equities keep rising on the heels of unprecedented stimulus and monetary intervention then Bitcoin is just along for the ride. The real test would come if equities enter a cycle of severe selling and to see Bitcoin then hold its own.

And looking at the chart above it appears we’ve had that test twice already. In 2018 when markets dropped Bitcoin dropped. In 2020 when markets dropped in February/March Bitcoin dropped along with them. Although in Bitcoin’s favor is that Bitcoin did not make new lows versus 2018 while markets clearly did. So one could make the argument it has already proven relative strength in this sense.

My general view here: Bitcoin will remain a successful speculative asset as long as equities keep rising and confidence can be maintained and accelerated. So far Bitcoin has proven it can outpace equities on the way up. The claim that it is a hedge against fiat printing remains, in my view, an unproven myth as of yet. That said, I wish everyone involved continued success in their endeavors, be it stamp collecting, wine collecting or Bitcoin collecting.

Tyler Durden

Fri, 03/26/2021 – 10:59

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/3d5VGek Tyler Durden