Authored by Alexander Rubinstein & Jeb Sprague via The GrayZone.com,

The longest piece of legislation in United States history, containing both a coronavirus relief package and the annual omnibus spending package, quickly passed through Congress on December 22, with little opposition. While technically separate bills, the omnibus and stimulus were debated and passed together, at the same time.

The massive piece of legislation – a staggering 5,593 pages in length – lays bare the priorities of the US government, prioritizing regime change in foreign nations and the imperatives of empire over the basic needs of Americans. In just a few hours, it passed through the House of Representatives by 359-53, and through the Senate by 92-6.

While the US public was forced to grovel for months for a $600 direct payment, the same piece of legislation pumps billions of dollars into “democracy programs” – US government code for regime-change operations via civil society NGOs – and foreign military assistance. The measly $600 survival checks pale in comparison to the massive foreign spending on regime change and titanic allocations to prop up US-friendly authoritarian militaries.

On so-called “Democracy Programs” alone, the legislation appropriates $2.417 billion, and $6.175 billion on the “Foreign Military Financing Program.” Another $112.9 million is appropriated for “International Military Education and Training.”

$6 billion more is allocated toward the domestic procurement of US Air Force missiles and US Navy weapons of war. This is in addition to the $740 billion defense bill passed earlier in December.

By contrast, the stimulus package comes at a value of $900 billion, with the largest portion devoted to business bailouts. The Federal News Network reports that the $1.4 trillion omnibus includes $671.5 billion allocated to “base defense spending,” with another $77 billion going to “overseas contingency operations.”

Stimulating regime change and intervening in the Global South

The legislation stipulates: “$300,000,000 shall be made available for a Countering Chinese Influence Fund to counter the malign influence of the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Chinese Communist Party and entities acting on their behalf globally.”

In Hong Kong, where CIA cutout the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) has given financial support to activist groups leading riots that rocked the city for months on end, the United States is now devoting $3 million for local destabilization efforts, including “internet freedom,” activists’ legal fees, and “democracy programs.”

Similarly, the legislation devotes $8 million to NGOs for activities in Tibet or to support the Tibetan government-in-exile. It appears that, every fiscal year between 2021 and 2025, it allows for the additional appropriation of $8 million per year to support Tibetan communities in Tibet, as well as $6 million per year to support them in Nepal and India, and another $3 million per year for “Tibetan governance.”

The bill also allocates $3.3 million for the US government-backed media outlet Voice of America, and $4 million to the similarly operated Radio Free Asia every year between fiscal years 2021 and 2025, in order “to provide uncensored news and information in the Tibetan language to Tibetans, including Tibetans in Tibet.”

In perhaps the most bizarre appeal to a regime-change activist lobby, an entire section of the bill is devoted to defining US policy “regarding the succession or reincarnation of the Dalai Lama.”

The bill also directs the secretary of state to establish a US consulate in Tibet.

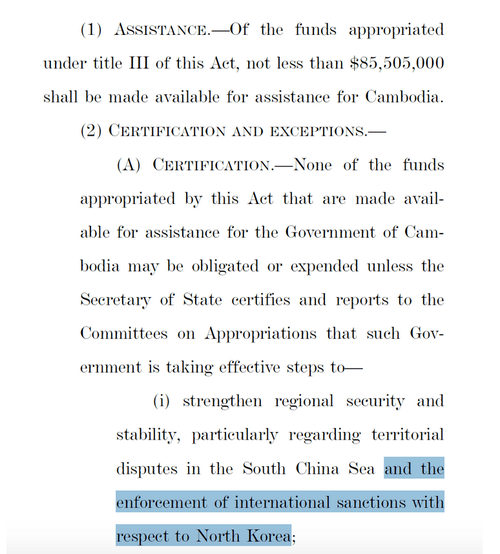

Meanwhile, aid to a number of countries is conditioned on their taking part in Washington’s economic aggression. For example, $85.5 million in assistance to Cambodia is contingent on it “taking effective steps” to enforce “international sanctions with respect to North Korea,” and “assert[ing] its sovereignty against interference by the People’s Republic of China.”

As for Latin America, the legislation stipulates that “not less than $33,000,000 shall be made available for democracy programs for Venezuela.” By contrast, the legislation appropriates $461.3 million for Colombia, a country which has seen massacre after massacre and scores of political assassinations — with more than 290 human rights activists killed in 2020 alone.

While 20 percent of the funds are not releasable until Colombia shows it is “taking effective steps to hold accountable perpetrators of gross violations of human rights in a manner consistent with international law,” given Washington’s record in the country, it will likely give the green light regardless of the facts on the ground.

Globally, $70 million is made available to support “internet freedom,” with an additional $2.5 million potentially available “to surge Internet freedom programs in closed societies.”

Meanwhile, a Ronald Reagan-inspired program aimed at expanding US influence and the “war on drugs” in the Caribbean, the Caribbean Basin Security Initiative, is being given a $74.8 million injection.

In Zimbabwe, where former President Robert Mugabe passed away in 2017, the government is still not off the hook. The legislation states: “The Secretary of the Treasury shall instruct the United States executive director of each international financial institution to vote against any extension by the respective institution of any loan or grant to the Government of Zimbabwe.” This language is aimed at depriving the cash-strapped African nation of international relief.

$15 million is going toward “democracy programs” in South Sudan, while $60m is being repurposed away from the “Global War on Terrorism” and “made available for assistance for Sudan”.

In central Africa, $325 million is being earmarked for assistance to Congo, with some part of this appearing to be intermingled with “peacekeeping” operations.

The phantom Russian menace

With $453 million appropriated for assistance to Ukraine, $290 million for “countering Russia,” $173 million for NATO, and $132 million for NATO ally Georgia, the legislation comes close to appropriating a billion dollars toward new cold war policies against Moscow.

The rationale for this spending may be the re-emergence of an old menace; a hint buried more than 5,000 pages into the document states that it is US policy “to not recognize any incorporation of Belarus into a ‘Union State’ with Russia, since this so-called ‘Union State’ would be both an attempt to absorb Belarus and a step to reconstituting the totalitarian Soviet Union.”

In one striking example of how hell-bent the legislation’s authors are on regime change and confronting Russia, the following phrase appears verbatim nine times: “The Government of Belarus, led illegally by Alyaksandr Lukashenka.”

The legislation also demands a report from the director of national intelligence, the secretary of state, and the secretary of treasury that identifies all of Lukashenka’s assets and those of his family, plus “identification of the most significant senior foreign political figures in Belarus, as determined by their closeness to Alyaksandr Lukashenka.”

The insistence on such information seems aimed at fast-tracking a list of entities to impose sanctions, in an effort to destabilize the country and make it ripe for a takeover by the US- and EU-backed opposition leader Svetlana Tikhanovskay, whose name appears six times in the legislation.

Along with detailed attention on cyber activities in Belarus, the bill explains how US officials will put together a comprehensive strategy and cost estimate for carrying out various operations aimed at the country, one of which includes: “Expand independent radio, television, live stream, and social network broadcasting and communications in Belarus to provide news and information, particularly in the Belarusian language, that is credible, comprehensive, and accurate.”

Middle East madness

As the incoming administration of President-elect Joe Biden has promised not to condition aid to Israel in any circumstance, including potential annexation of the West Bank, Congress has rushed to pump the apartheid regime full of fresh cash.

Of the $6.1 billion appropriated for funding foreign militaries, a whopping $3.3 billion – more than half – “shall be available for grants only for Israel,” and must be “disbursed within 30 days of enactment of this Act.”

Additionally, it appears that $500 million is appropriated for “Israeli Cooperative Programs,” which includes weapons procurements.

While it is difficult to interpret different allocations and far-distanced portions of the legislation going to the same target, one thing is clear: loads of money has been appropriated to a far-away apartheid state, as Americans remain unprotected from rent-related water shutoffs under the legislation.

Meanwhile, any aid to the Palestinian Authority will be held up if its officials initiate or support any kind of investigation at the International Criminal Court (ICC) that seeks the prosecution of Israeli nationals for crimes against humanity.

In neighboring Syria, which has been constantly bombed by Israel since the outbreak of the foreign-backed proxy war against the country’s government, Congress has appropriated $40 million toward” non-lethal stabilization” – in other words, destabilization assistance.

While the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) has largely been defeated, $710 million to counter the group remains “available until September 30, 2022”.

Iran, meanwhile, is mentioned 22 times in the legislation.

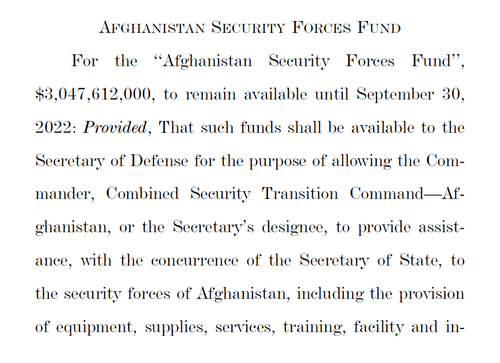

The ‘”Afghanistan Security Forces Fund” of $3 billion will “remain available until September 30, 2022,” and is geared toward the “security forces of Afghanistan, including the provision of equipment, supplies, services, training, facility and infrastructure repair, renovation, construction, and funding…”

The legislation also appropriates $250 million to reimburse the governments of Jordan, Lebanon, Egypt, Tunisia, and Oman on border security spending, with $150 million going to Jordan, a geostrategic lynchpin that shares a borders with Iraq, Israel, Syria, Saudi Arabia, and the Palestinian West Bank.

Another $241.4 million of appropriations through the “Department of State, foreign operations, and related programs” will be made “available for assistance to Tunisia.”

Egypt’s military, notorious for its repressive crackdowns on dissent, is due to receive a colossal $1.3 billion, according to the guidelines established in the Camp David Accords.

While US citizens continue to suffer the economic fallout of haphazard government shutdowns that have been largely ineffective in dealing with the coronavirus pandemic, Congress poised passed a greatly reduced stimulus packaged alongside a massive handout to corporate America and its foreign client states.

Now it is up to the outgoing president – ironically notorious for his ‘America First’ rhetoric – to sign the legislation into law. Reports indicate he intends to do just that.