On Tuesday, March 10, voters in five states went to the polls to cast primary election ballots, making former Vice President Joe Biden the Democratic Party’s all-but-certain presidential nominee in the process. It was probably the last approximately “normal” election night America will have this year.

That same day, the 1,000th positive test for COVID-19 was recorded in the United States. Over the next few days, professional and college sports leagues abruptly halted their seasons, and governors across the country were ordering schools, bars, and theaters to close, telling people to stay home whenever possible. A week later, on March 17, three other states held primaries in what was now anything but an ordinary environment. The 100th American to die of the disease passed away that night.

But on March 10, in that last moment of seeming normalcy, there was a sixth state which also had its primary votes tallied. In Washington state, more than 1.5 million people voted in the Democratic primary, and Biden squeaked out ahead by about 21,000 votes.

Nearly every vote was cast by mail.

In the middle of March, Washington conducting an election almost entirely by mail made it something of an oddity in American politics. By November, it will probably seem much more normal. The coronavirus has killed tens of thousands of Americans, ended the longest economic expansion in U.S. history, and forced us to reconsider every form of human interaction. Among them is the foundation of democratic society: voting.

Not all votes will be cast by mail or by absentee ballot in November. But the volume of what could be called “socially distanced voting” is going to be far higher than in any previous election. States, voters, media, and the election’s combatants may not be prepared for what that means.

As mail-in voting expands, it’s going to face political pressure from a president who is adamantly opposed to the practice, and logistical challenges from states attempting to build mail-in voting systems on the fly amid an already challenging environment. When Election Day finally arrives in November, it’s going to mean longer waits before all votes are counted—and possibly a longer period of uncertainty about who won—than ever before. Perhaps more worryingly, it could escalate distrust in a political system polarized to its breaking point.

President Donald Trump is already stoking fears about those uncertainties. “With Universal Mail-In Voting (not Absentee Voting, which is good), 2020 will be the most INACCURATE & FRAUDULENT Election in history. It will be a great embarrassment to the USA,” he tweeted in July. “Delay the Election until people can properly, securely and safely vote???” Republicans, however, were quick to reject Trump’s suggestion of delay. But the underlying issues remain. Like it or not, mail-in voting is coming—and we’re not ready.

“We are in times of high polarization, high distrust in elections, and we have a president who is fanning those flames,” says Richard Hasen, a professor of law and political science at the University of California, Irvine. “COVID[-19] has put incredible stresses on the election system—and would have even in the best of times, but we are not in the best of times.”

Voting by Mail Is Nothing New

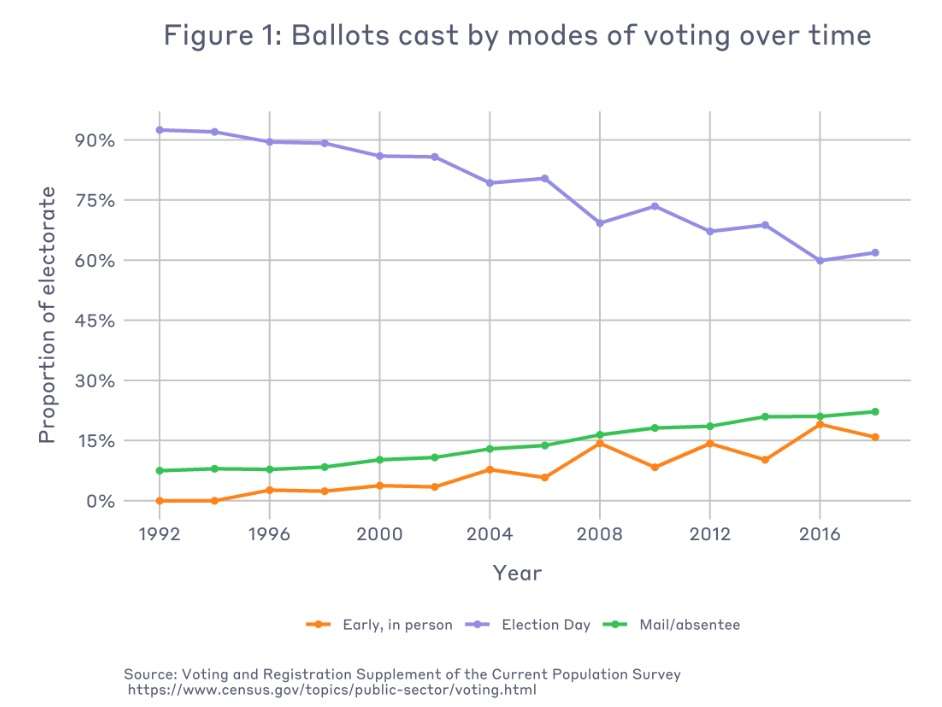

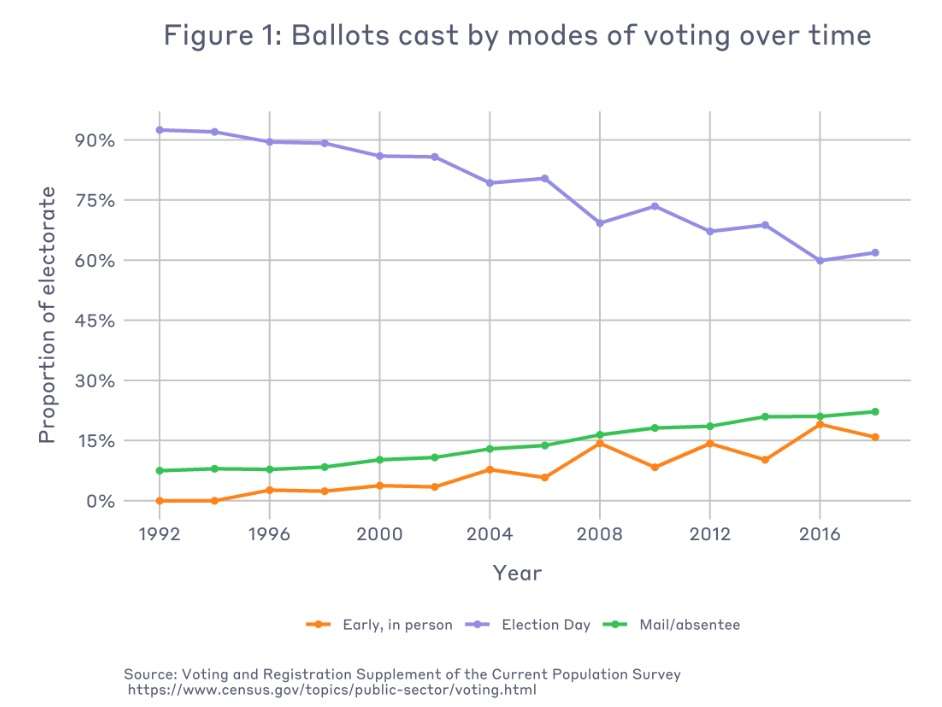

The pandemic hasn’t really caused mail-in voting to pop up out of nowhere so much as it has accelerated a trend that was already occurring. In much the same way that the pandemic has sped up the already ongoing shift towards more working from home, it is likely to nudge states to encourage more people to vote from home, too.

But voting by mail is “not a newfangled idea,” says Wendy Weiser, director of the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center for Justice. “It was already deeply embedded in the American electoral system before the coronavirus hit.”

In fact, the practice dates back to at least the Civil War, when soldiers on both sides of the conflict were allowed to vote in their home states, by mail, from wherever they happened to be camped at the time. According to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) Election Data and Science Lab, the first absentee voting laws for civilians were passed in the 1880s to accommodate voters who were incapacitated or away from home on Election Day. It wasn’t until the 1980s that states began to pass laws allowing residents to vote by mail without giving an excuse. Think of that approach as a de facto vote-by-mail-if-you-want-to system—a way of simply giving voters a choice about how to cast their ballots.

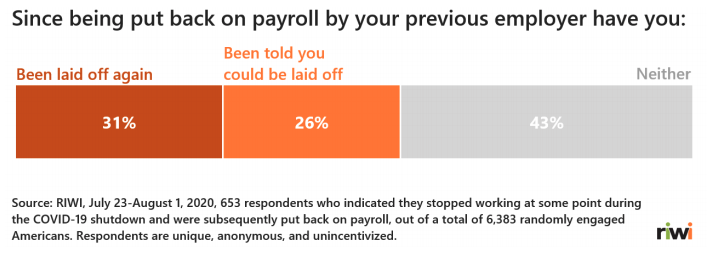

A lot of voters took that option even before the pandemic came along. In the 27 states and Washington, D.C., that had such laws on the books in 2018, more than a quarter of voters chose to vote by mail, compared to just 9 percent in the states where getting an absentee ballot requires explaining to the government why you need one, according to MIT’s data.

In a smaller set of states, the government simply mails a ballot to all residents prior to the election, no request necessary. Oregon pioneered that system, thanks to a ballot measure passed in 1998. Since then, Colorado, Hawaii, Utah, and Washington state have also moved to mail-based elections—that is, all voters receive a ballot in the mail, though they are free to vote in-person if they choose to do so instead. In California, state law allows county election offices to send ballots directly to all voters and have them returned via mail, but not all counties have made the switch. Several other places, including Arizona, Minnesota, and D.C., have policies that allow voters to request absentee ballots for all future elections, effectively letting individual voters opt into a permanent mail-in voting status.

In all, about 250 million votes have been cast by mail since 2000 according to the Vote At Home Institute, a nonprofit that advocates for expanding access to mail-in balloting. Along with the rise of in-person early voting, mail-in voting has contributed to a marked decline in the number of votes cast the traditional way: behind a curtain in your local elementary school on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November.

“If the actions of public officials are any guide, the truth is that by-mail voting has broad bipartisan support at the state level,” writes Edward Perez, global director of technology development for the Open Source Election Technology Institute, a California-based nonprofit that advocates for the use of tech to make America’s elections more secure. “The practice is well-established, increasingly popular, reliable, and neutral in its partisan effects.”

Still, the few states that did try to hold primary elections after mid-March provided a preview of what could happen in November if most Americans have to go to the polls. In Wisconsin, the Republican-controlled state legislature blocked an attempt by Democratic Gov. Tony Evers to postpone the state’s April 7 primary. More than 50 people who voted in person or worked the polls later tested positive for COVID-19. Georgia’s June 9 primary election broke turnout records despite the pandemic, but poll workers calling in sick and polling places that had to be relocated at the last minute to accommodate social distancing requirements were blamed for long lines and confusion among voters.

A swift move toward more mail-in voting could alleviate some of those risks. Unfortunately, states aren’t only facing practical, logistical, and public health challenges as they prepare for the election; they’re up against a big political hurdle, too. And time is running out.

Trump vs. Mail-in Ballots

“I think a lot of people cheat with mail-in voting,” Trump said in early April during one of the White House’s short-lived daily coronavirus briefings. He’d been asked about whether he thought Wisconsin should go ahead with its primary election and whether Americans should be prepared to vote by mail in November.

The president was adamant. “It shouldn’t be mail-in voting. It should be you go to a booth and you proudly display yourself. You don’t send it in the mail where people pick up—all sorts of bad things can happen by the time they sign that, if they sign that, by the time it gets in and is tabulated. No. It shouldn’t be mailed in.”

In the days and weeks that followed, Trump launched a full assault on the idea that Americans might embrace alternatives to queuing up at the polls on Election Day. More mail-in voting would produce fraud, he wrote in one particularly hyperbolic tweet on May 27, adding that “mail boxes will be robbed, ballots will be forged & even illegally printed out & fraudulently signed.”

It also might result in “levels of voting” that were disadvantageous to Republicans, he said during an appearance on Fox & Friends.

Since then, the Republican National Committee and the Trump campaign have launched a legal effort aimed at stopping mail-in balloting in states that are trying to expand it. In August, just days after raising the possibility of delaying the election in order to prevent what he argued would be “fraudulent” results, Trump even floated the possibility of an executive order aimed at curbing mail-in voting, though he has so far provided few specifics.

If mail-in voting is a Democratic plot to undermine Republicans’ chances at winning in 2020, that would come as news to many Republicans. When Colorado, for example, switched to providing ballots by mail in 2013, the process was overseen by Secretary of State Wayne Williams—a Republican.

A Reuters/Ipsos poll in April found that 79 percent of Democrats and 65 percent of Republican voters favored expanding mail-in voting for the general election. But Trump’s campaign against the alternative to in-person voting may have already had an impact. A July survey from the Pew Research Center found that 65 percent of Americans believed voters should be allowed to vote by mail without giving an excuse, but Democrats (83 percent) were far more likely than Republicans (44 percent) to say so.

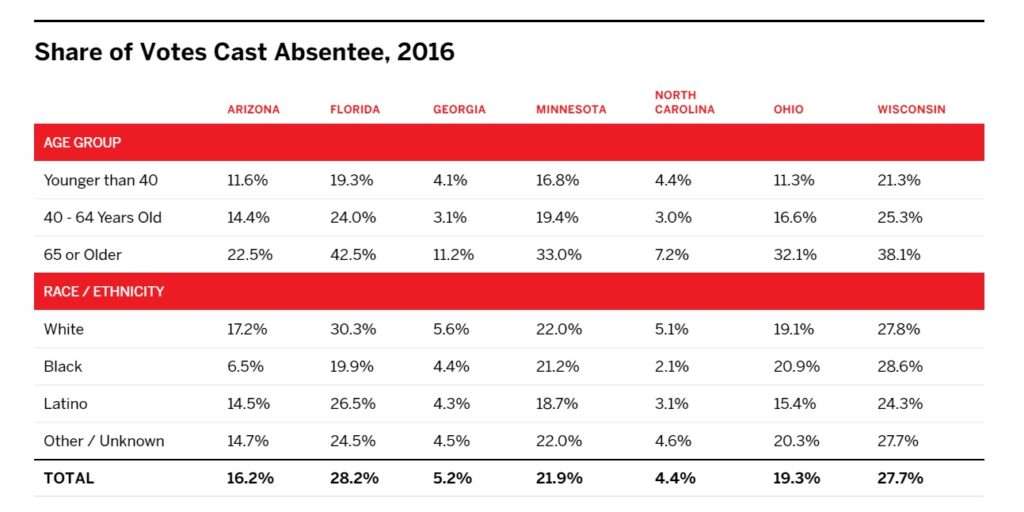

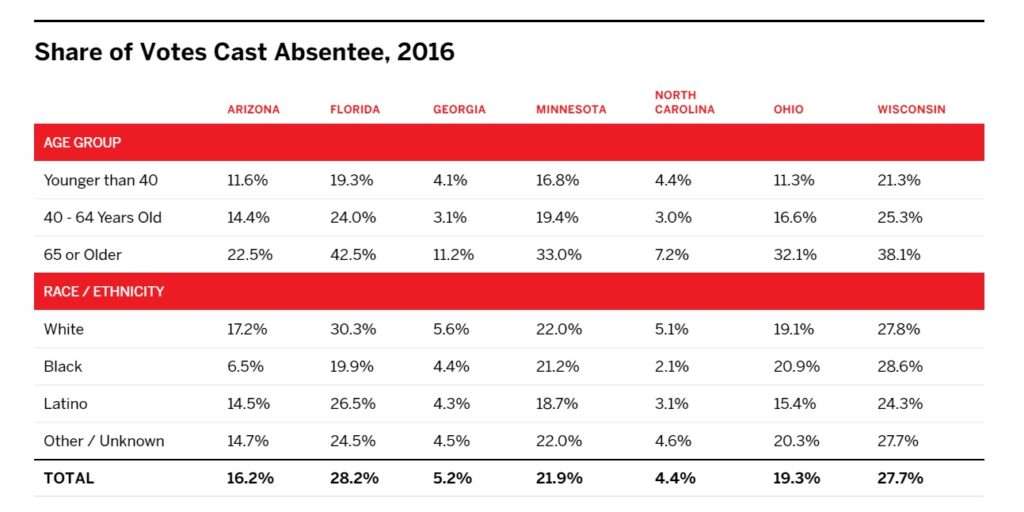

It’s true that studies have found an increase in turnout in states that have shifted to vote-by-mail policies, but absentee balloting doesn’t seem to favor either party. A Stanford University study released earlier this year that looked at absentee balloting since 1996 in California, Utah, and Washington concluded that “claims that vote by mail fundamentally advantages one party over the other appear overblown.” And a Brennan Center analysis of voting patterns in seven swing states that offered no-excuse absentee balloting in 2016 found that the people most likely to vote by mail were white voters over the age of 65—a key Trump demographic.

The idea that Republicans are disadvantaged by higher turnout is “nonsense,” says Tom Ridge, the former Republican governor of Pennsylvania and former Secretary of Homeland Security under President George W. Bush. Ridge, who now serves as chairman of the National Organization on Disability, says there is no reason for states to force voters to choose between “your health or your vote” and stresses that political parties should feel an obligation to support policies that make it easier for Americans to participate in the electoral process, regardless of whether there is a pandemic.

When it comes to the gamesmanship of politics, Ridge wonders if Trump’s repeated questioning of the legitimacy of mail-in voting could even end up hurting Republicans in the fall. If COVID-19 is raging in November, older voters that haven’t requested an absentee ballot (or who weren’t allowed to get one) might just stay home.

“Absentee voting gives neither party a political advantage, but the political party or the candidate that has a concerted, focused effort on encouraging absentee voting does have an advantage,” he says. “It seems counterintuitive and counterproductive for the president to be opposed to it when, frankly, Republicans are going to have to use it.”

Indeed, in a close election the marginal cost of Trump’s denouncements of voting by mail could haunt Republicans. As of mid-June, registered Democrats in Florida had requested roughly 300,000 more absentee ballots than registered Republicans—a gap that the state’s Democratic Party chairman attributed, in comments to Politico, to Trump’s success at tamping down Republican enthusiasm for voting by mail.

In North Carolina, the number of absentee ballot requests received by the state’s election board through July 27 was running nearly five times ahead of 2016’s pace, according to data collected by Old North State Politics, a North Carolina political blog. But while Republicans and Democrats were equally likely to request absentee ballots in 2016, 54 percent of requests this year have come from Democrats versus just 11 percent from Republicans (the rest came from registered independents).

The president’s hostility towards voting by mail—and what seems to be hardening partisan views about the process—is built atop a long-running conservative campaign against the perceived threat of voter fraud. The Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, maintains a Voter Fraud database containing more than 1,200 cases of voter fraud over the past four years. The list includes “impersonation fraud at the polls; false voter registrations; duplicate voting; fraudulent absentee ballots; vote buying; illegal assistance and intimidation of voters; ineligible voting, such as by aliens; altering vote counts; and ballot petition fraud.”

Clearly, then, in-person voting is no guarantee that fraud will not take place. Still, conservatives like Hans von Spakovsky, a senior legal fellow at The Heritage Foundation and head of the think tank’s election fraud initiative, worry that an increase in mail-in balloting will create more opportunities for fraud. “Mail-in ballots are completed and voted outside the supervision and control of election officials and outside the purview of election observers, destroying the transparency that is a vital hallmark of the democratic process,” he wrote in a report released on July 16 which warned that “encouraging even more mail-in voting and relaxing security protocols, such as witness or notarization requirements, is a dangerous policy.”

Widespread voter fraud would undermine the legitimacy of elections, and therefore must be taken seriously. But the evidence shows that voter fraud rates are “infinitesimally small,” says Weiser, and that’s true for mail-in balloting too. One analysis of absentee balloting from 2000 through 2012 found 491 cases of fraud—about 0.0000001 percent of all votes cast that way.

The main reason why voter fraud is so rare is that individual votes are worth very little, but the punishments for getting caught voting fraudulently are serious. That’s true for both in-person voter fraud and the mail-in variety. In Oregon, for example, mailing a fraudulent ballot can land you in prison for five years.

On top of the deterrent value of harsh penalties, the states that have adopted mail-in balloting use a variety of methods to prevent and detect fraud—and to provide voters with the assurance that their ballots are counted.

Those strategies mostly fall into three categories: technology, tracing, and transparency.

In Colorado and Oregon, unique bar codes attached to each ballot mailed ensures that voters aren’t duplicating their ballots and returning more than one. Additionally, all absentee ballots must be signed by the voter, and those signatures are compared to voter rolls—or, in some states, lists maintained by the Department of Motor Vehicles—by signature-matching software.

Tracing takes place after the election is over, and experts say it’s one of the ways mail-in balloting can be more secure than the electronic voting machines used in some states. Voting by mail leaves a literal paper trail for post-election audits to follow. In 2018, for example, a canvass of absentee ballots in North Carolina caught one of the few recorded incidents of large-scale voter fraud in recent history—orchestrated by a Republican political operative—and the election was re-run.

By comparison, the Senate Intelligence Committee’s investigation into potential Russian interference in the 2016 election found that 13 states use voting machines that don’t provide paper records for post-election checking. There’s no indication that foreign governments hacked the vote in 2016, but the lack of a paper trail means it can be harder for election officials to detect more mundane problems too. Mail-in voting solves that.

Finally, the whole process is transparent. Don’t trust the post office to deliver your ballot to the county election office? Even states that have converted to full vote-by-mail elections give voters the option of dropping off their ballots in the weeks leading up to an election. A Harvard University study of the 2016 election found that 73 percent of voters in Colorado and 59 percent in Oregon returned their ballots via those drop boxes at local election offices.

“Trump’s claims are wrong,” says Weiser. “Mail ballot fraud is incredibly rare, and legitimate security concerns can easily be addressed.”

Indeed, Trump’s worries about mail-in voting seem somewhat hypocritical: Less than two weeks before his tirade against mail-in voting in April, Trump had voted with an absentee ballot in the Florida primary. His campaign’s official Twitter account blasted out a message in mid-May encouraging Wisconsin voters to apply for absentee ballots so they could vote in a special congressional election.

Get Ready for Chaos Anyway

The bigger problem facing states as they prepare for the 2020 general election is not the president’s tweeting or the spectral fears of voter fraud. It’s that there is no time to build out the infrastructure necessary for a full-scale vote-by-mail operation like the ones in Colorado, Oregon and elsewhere.

So far, Congress has authorized $400 million in new spending to help states get prepared for what’s likely to be the weirdest election in recent history, but the Brennan Center says it will take $4 billion in additional election spending to cover the cost of ballot printing, postage, security measures like drop boxes and bar codes, and hiring additional staff to count votes. Hasen estimates that, despite spending more than $3 trillion on coronavirus aid, Congress has provided to states only about 20 percent of what would be necessary to run an election in the middle of a pandemic—meaning not only expanded absentee balloting, but also funding for things like protective equipment for poll workers.

But money can’t buy time, which is what states really need right now. “We’ve been at it for a decade. It’s not an easy lift to make that transition,” Julie Wise, the director of elections for King County, Washington, which includes Seattle, told Cascade Public Media in April.

The Vote At Home Institute provides state officials with an 18-step process for making the transition—it involves not only designing, printing, and mailing ballots, but informing voters of the changes as well as creating the necessary infrastructure to receive and count all those votes in a timely manner. And, of course, implementing measures to detect and prevent fraud.

States that have taken action in the interim have mostly moved to do away with restrictions on who can get absentee ballots. In New Hampshire, for instance, all voters will be allowed to request absentee ballots and list “COVID-19” as a valid excuse for not showing up at the polls.

A few others, like Illinois and Massachusetts, have decided to automatically send absentee ballots to all eligible voters at their last registered address. Wisconsin will send absentee ballot request forms to all voters, and make absentee ballots available to anyone who fills out and returns the paperwork.

Expanding no-excuse absentee balloting is probably the best that many states will be able to do before November, but even that relies on overcoming political opposition. “Fear of contracting COVID-19 does not amount to a sickness or physical condition as required by state law,” Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton said in a statement last month announcing that the state would not expand access to mail-in voting. His office promised to prosecute individuals who use absentee ballots in an “improper manner.”

Even in the vast majority of states that have moved to ease restrictions on absentee balloting in light of the pandemic, a full-scale vote-by-mail system is virtually impossible to implement before November. Weiser advises that “accessible in-person voting sites” should be maintained even as counties and states try to encourage more voting from home. That’s “for those who cannot or will not vote by mail and as a fail-safe to the inevitable problems that may arise.”

Depending on the status of the pandemic in early November, that might be what most voters choose to do. Even though polls consistently show support for expanding mail-in voting, a July poll by ABC News and The Washington Post found that 59 percent of Americans would prefer to vote in person.

Problems will almost certainly arise, as they have in the past. The 2000 presidential election dragged on for weeks after Election Day as a Florida recount became fixated on questions about “hanging chads” and other unusual ballots; ultimately the outcome was decided by the state Supreme Court. Smaller ballot-counting glitches plagued this election season, even before COVID-19.

On February 3, the Iowa caucuses descended into pandemonium when a glitchy computer program made it impossible for the state Democratic Party to get accurate results from caucus sites. It took three days for the final results to be reported. That’s three days to count votes in one small state’s primary election—an election that everyone knew wasn’t going to settle anything. Two different candidates gave victory speeches—or speeches that seemed a lot like victory speeches, at least—and cable news was aflutter with speculation about what it all meant.

Now imagine if the outcome of the presidential election—or control of Congress—had been hanging in the balance. “Florida in 2000 might look like a picnic compared to this,” says Hasen.

As it happened, Hasen’s book Election Meltdown was released on the same day as this year’s Iowa caucuses. “It was good product placement,” he jokes. Timely as it might have been, that night was also a wake-up call for election officials and academics. Three weeks after the meltdown in Iowa, Hasen hosted a hastily organized conference at University of California, Irvine, with the goal of making suggestions for how states could better secure the legitimacy of the 2020 general election. In mid-April, the group released a report with 14 suggestions ranging from expanding mail-in and early voting options to informing the public about the potential delays in reporting results.

The goal of expanded voting-by-mail is not to abolish voting booths and the traditional democratic process it represents. It’s to give voters more options, allow more people to participate, and—particularly this year—to cut down on long lines and crowded polling places. Every ballot cast through the mail is one fewer person who will have to stand in line on Election Day.

The trade-off is that absentee ballots typically take days, sometimes weeks, to be counted. Georgia, New York, and other big states that relied heavily on voting-by-mail for primary elections during the late spring and early summer experienced long delays in reporting official results. It took New York more than a month to finish counting all its absentee ballots.

“The U.S. has never had to shift its system of election administration so massively and so swiftly,” wrote Nathaniel Persily, a law professor at Stanford University and co-director of the Stanford-MIT Healthy Elections project in a June op-ed for The Wall Street Journal.

He cautions that patience will be necessary. The number of absentee ballots cast in several primary elections during the spring and early summer overwhelmed local election offices and led to delays in posting official tallies. That’s likely to happen again in November. Tens of millions of ballots might remain uncounted on election night, and a “winner may not be known for days.”

Compounding the logistical problems is simple voter ineptitude. In-person voting limits common mistakes—like voting for too many candidates or failing to sign a ballot—that are more likely to happen with absentee ballots. Research by Charles Stewart, a professor of political science and founder of the MIT Election Lab, an estimated 800,000 absentee ballots were rejected in 2008 by local election authorities, mostly due to mismatched signatures or because they arrived too late. Counting absentee ballots requires reviewing them one-by-one, and even though computers help, much of the work is still done by hand (and that’s especially true in states without a true vote-by-mail infrastructure in place).

In 12 states—including the key presidential swing states of Pennsylvania and Michigan—officials are forbidden by state law from counting absentee ballots until Election Day, even if they arrive days or weeks in advance. That means those states won’t be able to get a head start on what’s sure to be a dayslong or weekslong process.

Mail-in balloting will make Election Day effectively last days or even weeks after voting as concluded, but it will also stretch it forward in time too. In late July, a viral meme circulating on social media advised mailing ballots back to election offices no later than October 20. It’s probably not necessary to put your vote in the mail quite that early, election officials say, but allowing enough time for delivery is important.

What it all means is that, in every regard, the mechanisms of this year’s election are going to take more time than usual.

Election Night(s) in America

Elections accomplish many different things. They are the only poll in politics that really matters, the one that signals what the public wants or what it wishes to stop. They confer legitimacy on the government’s power to tax, regulate, and police us. They make careers and end them—not just for politicians, but for everyone who helps get them elected or defeated.

But they can only accomplish those tasks if they are viewed as being more or less legitimate exercises conducted with impartial rules and producing accurate results. Every American election is a bit of a mishmash due to overlapping local, state, and federal districts and varying rules across 50 states and more than 100,000 precincts. But regardless of how exactly it works where you live, the important thing is that it does.

This year, that patchwork of policies will be even more complex. The 2020 election has huge stakes, but it will also be a giant, and potentially messy, experiment. An increase in mail-in voting should not undermine the legitimacy of the 2020 general election. An estimated 33 million Americans voted by mail in 2016, and even if that total doubles or triples this year, it should not change how the results are viewed. But, legitimacy is in the eye of the beholder.

Patience is not a guiding principle in American politics. This year, it might have to be.

“We all need to be prepared to expect and explain a long vote count in the days and perhaps weeks following Election Day,” says Kyle Kondik, managing editor at the University of Virginia’s Center for Politics. Election Day could end up being “a mess,” he says, if polling places have to be closed at the last minute due to outbreaks and if it isn’t feasible for states to expand early voting or vote-by-mail options.

“I fear it’s going to be difficult,” he adds, “and that conspiracy-mongering will fill the void of an uncalled election.”

Hasen worries that some results might change in the days or weeks after Election Day as absentee ballots are processed and counted. That happened in 2018, when two congressional districts in southern California were ultimately won by Democrats despite the fact that Republicans had initially appeared to prevail. “There was nothing nefarious going on,” says Hasen, there were simply more Democrats who voted by absentee ballot, as allowed under California law. But, he adds, “I think we can certainly expect to see a similar pattern that is now exacerbated by the president discouraging his supporters from voting by mail.”

And if there are major results—especially in the presidential race—how will Trump respond if a flood of absentee votes tip the election days later? His recent tweets suggests he’s prepared to use the delays created by mail-in voting to raise questions about the legitimacy of the election’s outcome. “Must know Election results on the night of the Election, not days, months, or even years later!” the president tweeted on July 30. That’s a standard that would be nearly impossible to meet during normal times—even in years without Bush-Gore levels of controversy, close elections can remain uncalled for days. Federal law allows 35 days for election officials to certify results.

What should election officials do? Look at those same congressional races in California in 2018. Orange County was transparent about how many absentee ballots had been received and about how long it would take to tally them. Everyone involved knew the race wasn’t going to be settled by the end of the night, and that helped prevent the appearance of a major scandal.

“Transparency is important. Competence is obviously important,” says Hasan. “And that stuff needs to happen now. You can’t do it on the fly. The rules and procedures have to be announced now, so it doesn’t look like you’re changing things at the last minute to help one candidate or another.”

The current level of political polarization does not inspire confidence in America’s ability to navigate a high stakes election under the best of circumstances. Barring some unexpected medical breakthrough, it seems like the 2020 general election will be conducted in far from the best of circumstances.

On August 4, the president added another twist to his weeks long campaign of griping about potential fraud and unnecessary delays associated with mail-in ballots. “Whether you call it Vote by Mail or Absentee Voting, in Florida the election system is Safe and Secure, Tried and True,” Trump tweeted. “Florida’s Voting system has been cleaned up (we defeated Democrats attempts at change), so in Florida I encourage all to request a Ballot & Vote by Mail!” At the same time, the Trump administration sued the state of Nevada over plans to mail ballots to every voter, following an accusation that the state’s governor had “made it impossible for Republicans to win the state.”

It is obviously not the role of the president to pick and choose which methods states can use to run elections—but it appears that Trump may have realized that his attempt to delegitimize mail-in balloting was backfiring.

Regardless of what Trump may between now and Election Day, voting by mail should not be subject to a partisan campaign of scare tactics designed to undermine the legitimacy of the election. The practice is already widespread, safe, and accurate.

Allowing more people to vote by mail if they choose is a good way to alleviate the public health risks presented by having an election in the middle of a pandemic. It is not, however, a guarantee of a controversy-free election. Indeed, nothing is. That’s why voters, candidates, and political junkies should be prepared for an election night that spills over into the next day, or even the following weeks.

But that’s all right—there won’t be any parties anyway.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3a8qXez

via IFTTT